And to the “Republic” for which it stands

My first encounter with the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition fairgrounds

How could an entire city just … vanish?

Soon after moving to Chicago in 2003, a colleague at the University of Chicago offered me a campus tour. He pointed out the open lawn running along the south end of its handsome Collegiate Gothic quad. “This is the Midway.” Seeing my blank stare, he continued: “From the World’s Fair?” I knew about the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition but had not realized it was held in this part of the city. “That’s where the Ferris Wheel used to be. The main fairgrounds were over there,” he added, pointing eastward past lines of parked cars.

As I looked down the empty stretch of grass toward the lake, incongruous images of the great Chicago fair clouded my view. Ornate Beaux Arts buildings decorated like wedding cakes, wildlife frozen on pedestals as white statues, and a golden colossus standing in the water with arms stretched toward the heavens. I also pictured that haunting picture on the cover of the book everyone (it seemed) was reading that summer. In coffee shops, on El trains, at the beach—Chicagoans were immersed in the fascinating story of The Fair That Changed America … and of some nearby devilry. Readers held in their hands a photograph of the illuminated Court of Honor, showing the black pool of the Grand Basin reflecting the glow from ghostly white palaces. Surely some vestige of this Dream City still existed in the old fairgrounds.

A few weeks later, I set out on bicycle to explore Jackson Park and hunt for remnants. Riding around the lone remaining exposition building (once an art palace, then a museum to the Fair, now a science museum) and past the east end of the empty Midway, I encountered more open lawns, an unused football field, some crumbling parking lots, and a golf course. Had a White City really once stood here?

Then I bumped into her.

The Ecstasy of Gold

It was not love, but obsession at first sight. In the center of a rather sad little traffic circle stood a radiant Golden Lady, glowing in the morning sunlight as she faced Lake Michigan. A statue twenty-four-feet tall on a handsome ten-foot pedestal made of pink granite. I instantly fell under the spell of this gleaming beacon of a lost city.

“The Republic—to commemorate the World’s Columbian Exposition MDCCCXCIII,” reads the inscription on the pedestal. This was all the invitation I needed. Later that day I picked up a copy of The Devil in the White City and emersed myself in the story of how the 1893 World’s Fair was built, experienced, and then dismantled.

I learned that the Golden Lady is not a relic from the great fair, but a replica. A little sister, actually. The original Statue of the Republic was almost three times larger and overlooked the 1893 fairgrounds from a spot about 1000 feet further east (now buried under South DuSable Lake Shore Drive). That colossus faced west, watching the American frontier vanish.

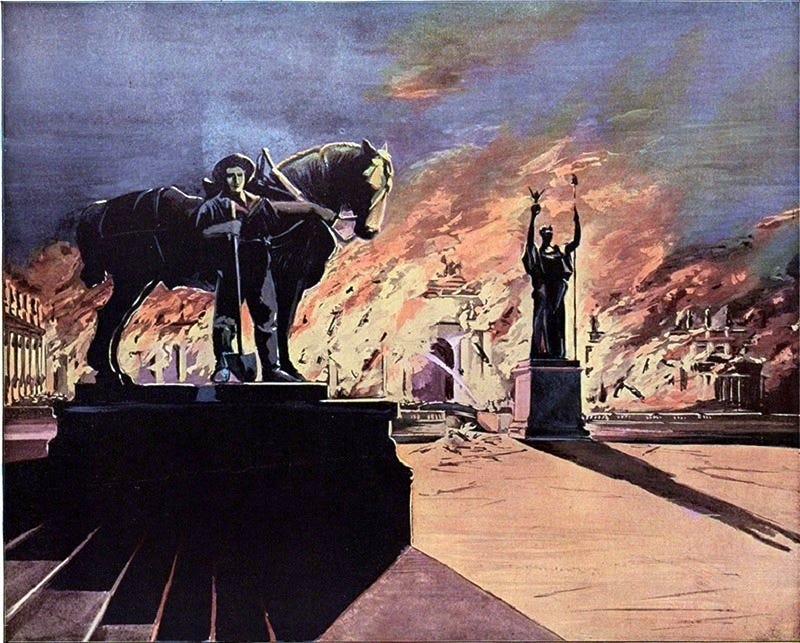

Daniel Chester French’s golden Statue of the Republic was the largest sculpture ever made in America at that time. (Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi’s Statue of Liberty is taller—151 feet from base to torch—but was made in his studio in France. Take that, New York.) Made of staff and covered in gold leaf, French’s colossal work was never intended to last much longer than the 1893 Fair, and it didn’t. After years of neglect and slow decay, she was put out of her misery in the earlier hours of August 28, 1896, when Chicago’s South Park Commission set the structure ablaze. Chicago lost one of the few remnants of the great Fair in Jackson Park.

Twenty years later, French cast a smaller near-facsimile statue made of gilded bronze and meant to last. With appropriate pomp and circumstance, officials installed this replica in 1918 to honor the 25th anniversary of the World’s Columbian Exposition and the centennial of Illinois statehood. Due to a redesign of Jackson Park, the replica was placed in a new location, almost exactly on the spot where a statue of Benjamin Franklin once stood at the entrance to the Electrical Building.

Besides being a third smaller than the original Statue of the Republic, the reproduction has another notable difference. Look at the top of the staff in her left hand. The 1893 version has a Phrygian cap (or “liberty cap”) resting on it. For the replica, French replaced it with a placard proclaiming LIBERTY joined to a torch and a laurel wreath. It’s a small change, but easy to spot when designers use this reproduction as their model for the statue from the Columbian Exposition (Looking at you, Joffrey Ballet).

Colossal Challenges

The bigger change was its placement. The inside of an isolated and isolating traffic circle doesn’t feel suitable for such a grand sculpture, especially with the increase in the number of cars since 1918. “The setting for the facsimile among trees and informal parkland is judged to be unflattering,” concluded Edward Campbell (“Jackson Park’s ‘Golden Lady’, then and now” Hyde Park Herald May 28, 2003) around the time Chicago’s City Council awarded the statue landmark designation. “Lacking the majestic court and classic buildings—the qualities that gave it beauty, focus and stateliness, it now seems out of place, an anachronism, an essence lost.” Trapped in a roundabout, the Republic is something to get around rather than a monument to approach and learn from.

Re-gilded and rededicated for the centennial of the Columbian Exposition, the new Republic remains the only major landmark in Jackson Park to commemorate Chicago’s great fair. This solitary sentinel has stood witness to many changes over the years beside just more cars, including a marina in front of her and the new Obama Presidential Center going up behind her. Jackson Park has slipped into more modern clothing while this gold brooch dangles like an awkward piece of vintage jewelry. Some have wondered if the time has come to remove it.

In 2021, the Republic (along with three other artworks from the 1893 Fair) underwent review by the Chicago’s Monuments Project advisory committee, charged with assessing city-owned statuary to “address the hard truths of Chicago’s racial history.” Anyone studying the Columbian Exposition must confront many uncomfortable and hard truths of that era … and of the one we live in. Honest scrutiny of this historic statue raises important questions. What does she represent? Who gets to decide? Is there room for different interpretations? Faring better than her big sister, the Golden Lady seems to have emerged from the review untarnished.

Despite threats of isolation and cancelation, the Statue of the Republic has developed into an icon of Chicago, though not quite up there yet with our lions or the young “Bean.” Images of Daniel Chester French’s Golden Lady decorate notecards, t-shirts, marathon medals, and several adult beverage containers. Fun, though not always decorous, reminders of Chicago’s great fair.

Each time I revisit the Statue of the Republic, the Vanished City that once stood around her becomes more visible in my mind’s eye, thanks to two fun decades of researching the wonders of the World’s Fair.

I also become a bit more melancholy about this golden symbol of the Columbian Exposition standing watch in a lonely traffic circle.

This is so great and the close-up of the head of the statue is breathtaking, Scott!